History Day 2009

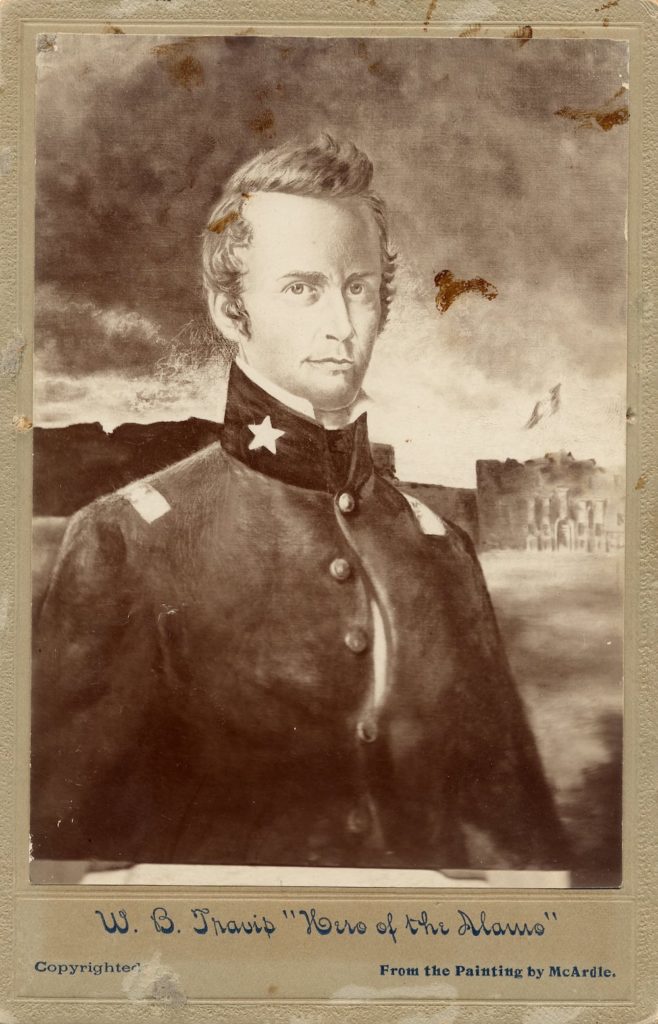

William Barret Travis

The second annual Travis County History Day was held on Friday, August 7, 2009, in honor of Travis County’s namesake, William Barret Travis, and to commemorate the establishment and formation of Travis County. Held in the Heman Marion Sweatt Travis County Courthouse, the event welcomed speakers Ronnie Earle, former District Attorney; Dr. Archie McDonald, noted author and historian; and Peggy D. Rudd, Director of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

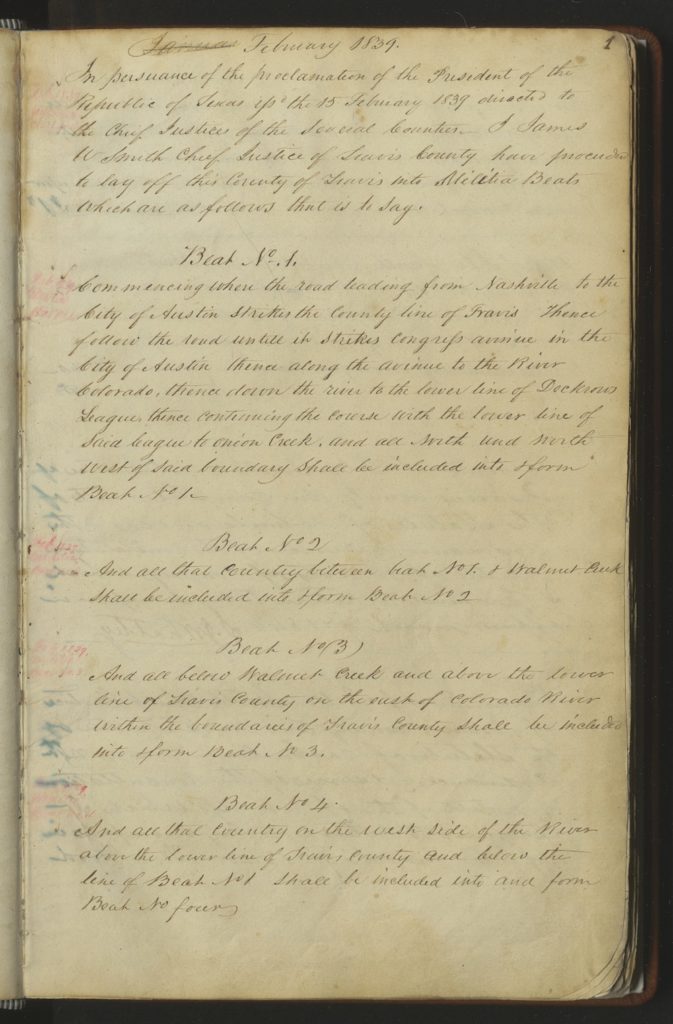

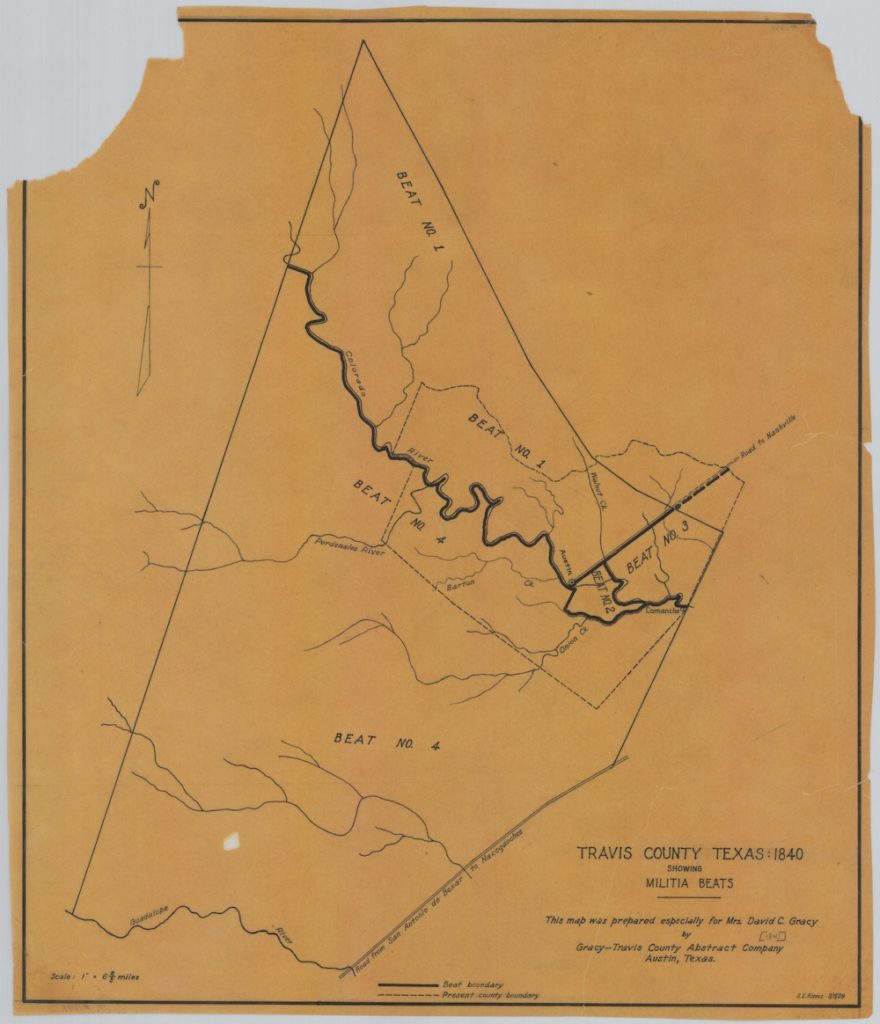

Travis County was established on January 25, 1840, by an act of the Fourth Congress of the Republic of Texas, days after the community of Waterloo had been renamed Austin and approved as the capital city. The county was in operation as early as 1839, prior to its official establishment. The first election for county officials was held in February of 1840, at which time the population was reported to be 856.

Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Travis County was created from Bastrop County, one of the original twenty-three counties formed in 1836. The encompassing area was known as the Travis District, which consisted of roughly 40,000 square miles. Counties that were later carved from the Travis District include Comal in 1846, Gillespie and Hayes in 1848, Burnet in 1852, Brown and Lampasas in 1856, and Callahan, Coleman, Eastland, Runnels and Taylor in 1858. Today Travis County comprises 989 square miles with a population of around one million.

William Barret Travis, namesake of Travis County, was in command of the Texan forces at the Battle of the Alamo, where he was killed along with his men. Although Travis likely never set foot in the area that was to become Travis County, it is not surprising that the Republic of Texas Congress chose him as the county’s namesake. The establishment of Travis County followed the fall of the Alamo by just a few years, and Travis’s sacrifice was still fresh in the minds of the Texans.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

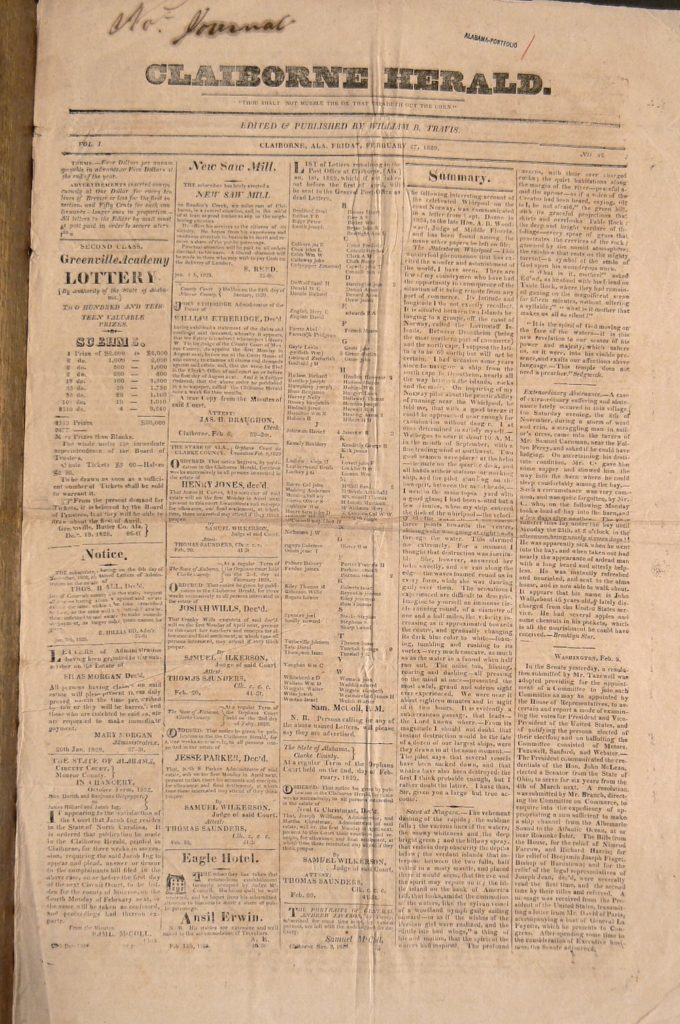

The eldest of 11 children, William Barret Travis was born on August 1, 1809, in South Carolina, and grew up in Alabama. In Claiborne, Alabama, Travis succeeded as a student, eventually becoming an assistant instructor at a school and later, a lawyer. He also began the publication of a newspaper, the Claiborne Herald. In 1928, Travis married Rosanna Cato, one of the students he had instructed. Their first child born the following year. All signs indicated that Travis intended to remain in Claiborne. However, just a year later, he unexpectedly abandoned his wife, son, and unborn daughter, and abruptly departed for Texas.

Library of Congress

Travis arrived in Texas early in 1831, and his first documented appearance was made in San Felipe de Austin, part of Stephen F. Austin’s colony in what was then Northern Mexico, where he applied for land and was admitted as a settler. Travis did not stay in San Felipe, but traveled further south to the less-populated Anahuac, a town that served as a port of entry for American settlers coming into Spanish territory. There Travis established his legal practice and began learning the laws of Mexico and the official language of Spanish.

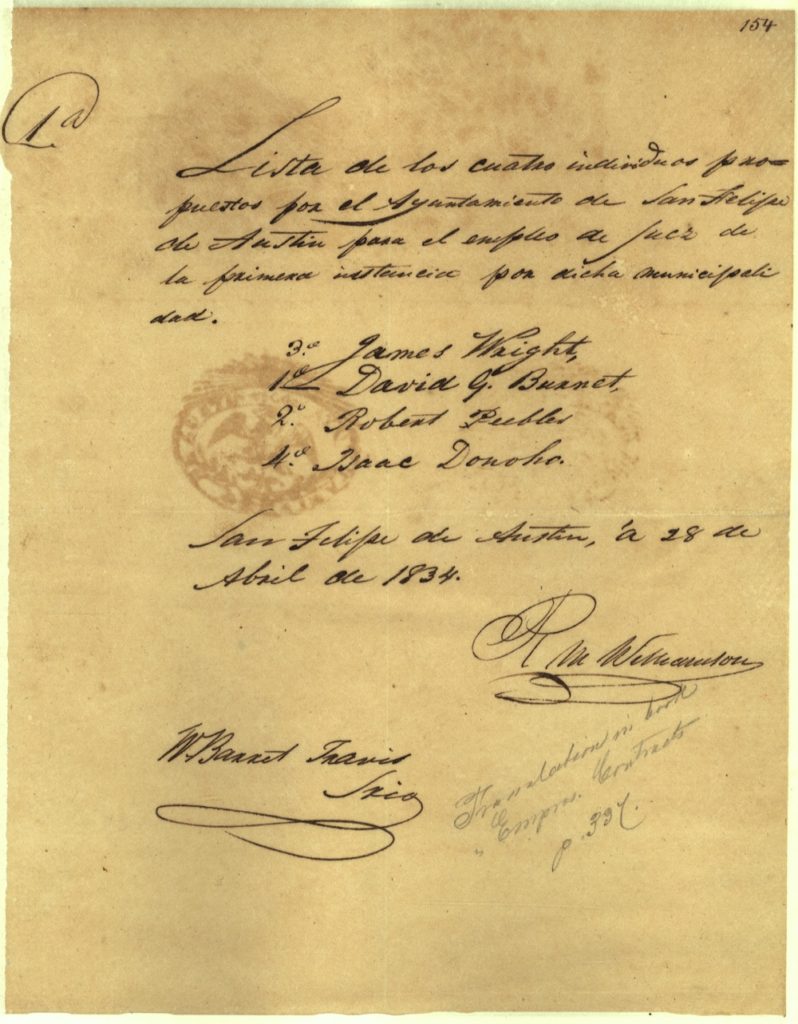

ayuntamiento with Travis’s signature, 1834

Texas General Land Office

By the early 1830s, the tension between the Anglo-American settlers and the Mexican government in Texas was rising. While many Texians hoped for peaceful resolution, others, such as Travis, pushed strongly for revolution. Travis became involved in a series of clashes known as the Anahuac Disturbances; while many Texians viewed Travis as a troublemaker, his status as a major figure in the events of the Texas Revolution was growing.

Travis moved his legal practice to San Felipe in the aftermath of the clashes at Anahuac, and there his professional activities and reputation as a leader continued to grow. In 1834, Travis was elected as secretary to the ayuntamiento, the principal governing body in San Felipe. Travis’s duties included putting into effect the orders and directives of the state and national governments.

In the fall of 1835, the tension between the Texians and Mexicans was reaching new heights. When Stephen F. Austin put out the call for soldiers in response to the arrival several hundred Mexican soldiers in Texas, Travis was ready to answer. By September 28, he was enrolled as a lieutenant in what Austin referred to as the Federal Army of Texas.

War began at Gonzales on October 1, 1835. When the Mexican army demanded the surrender of the Gonzales “come and take it” cannon, Travis joined the hundreds of Texians who hastened there. A more formal organization of the military forces soon followed, and on the 19th of October, Travis joined up with Stephen F. Austin and his forces. Austin’s army moved to within five miles of San Antonio to besiege the town. On October 27, Austin ordered Travis to raise a volunteer company of cavalry of his own to serve as a scouting and reconnaissance unit, and Travis was soon promoted to captain.

Texas General Land Office

In January of 1836, Travis was ordered to recruit men and reinforce troops at San Antonio for the impending arrival of General Santa Anna and the Mexican Army. James Bowie had also arrived at San Antonio, and he and Travis initially quarreled over command. They were able to affect an uneasy truce of joint command until an illness befell Bowie and forced him to bed, leaving Travis in sole command.

Travis directed the preparation of San Antonio de Valero Mission, known as the Alamo, for the arrival of Santa Anna. He helped strengthened the walls, constructed palisades to fill gaps, mounted cannons, and stored provisions inside the fortress. Santa Anna’s advance arrived in San Antonio on February 22, and despite numerous letters sent by Travis requesting aid, additional reinforcements for the Texians were nowhere to be seen.

Texas State Library and Archives Commission

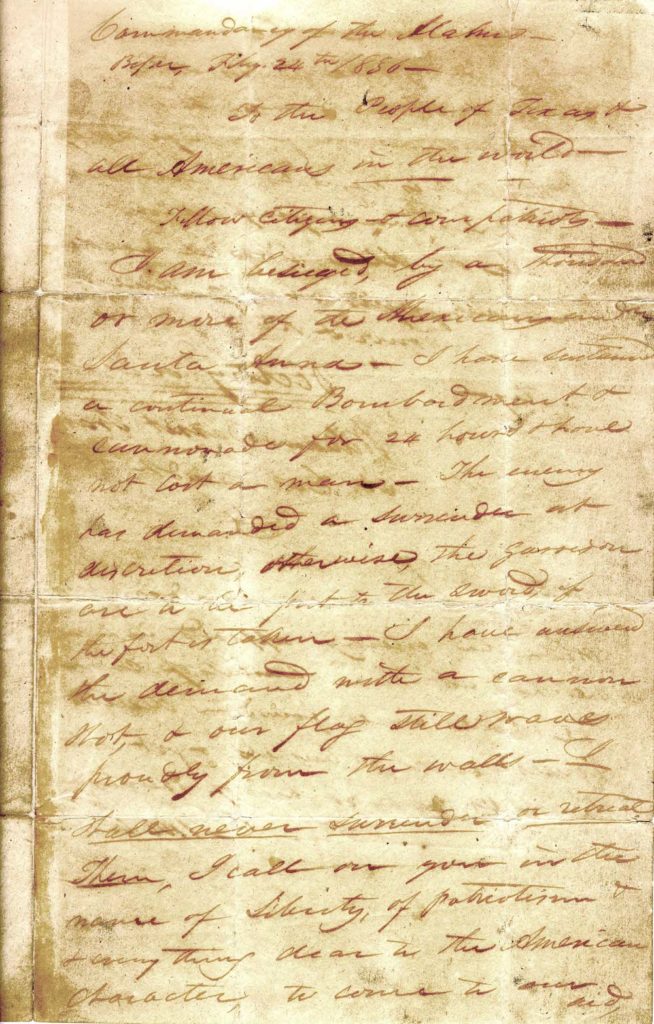

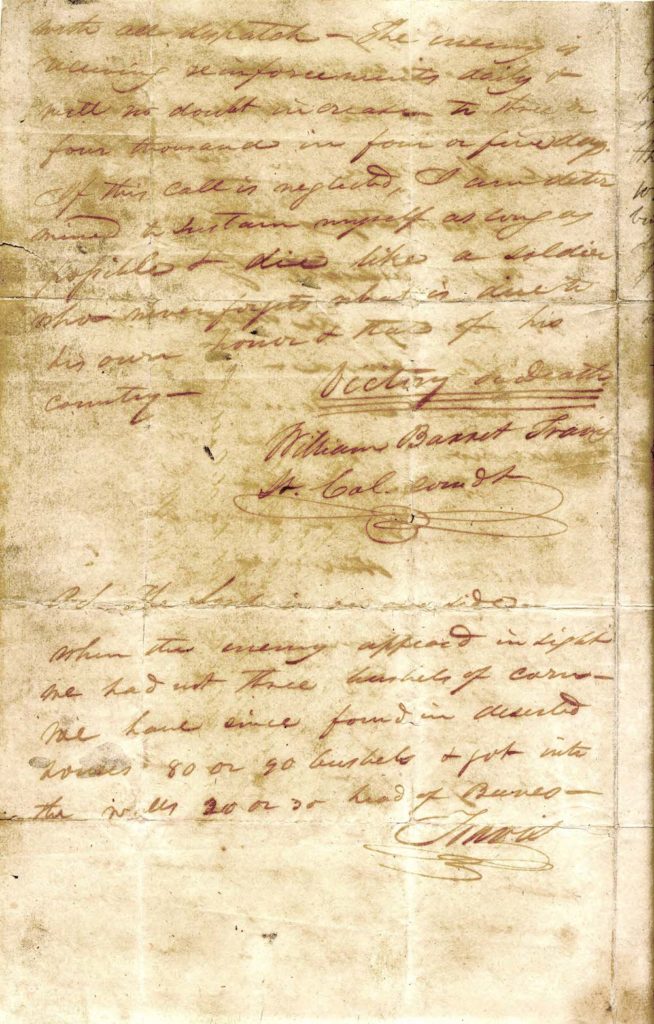

Two days into the siege, Travis penned his infamous “Victory or Death” letter. He continued to send letters requesting assistance, even as cannons began firing at the Alamo. Each letter was eloquently written and carried a similar message – the Mexican army had invaded Texas, the Alamo was surrounded, and the Texians needed more men and ammunition to wage a successful defense. Only an additional few dozen men came from Gonzales, however, and all in all, the Alamo had between 182 and 257 volunteers, both Tejano and Texian, to fight in its defense.

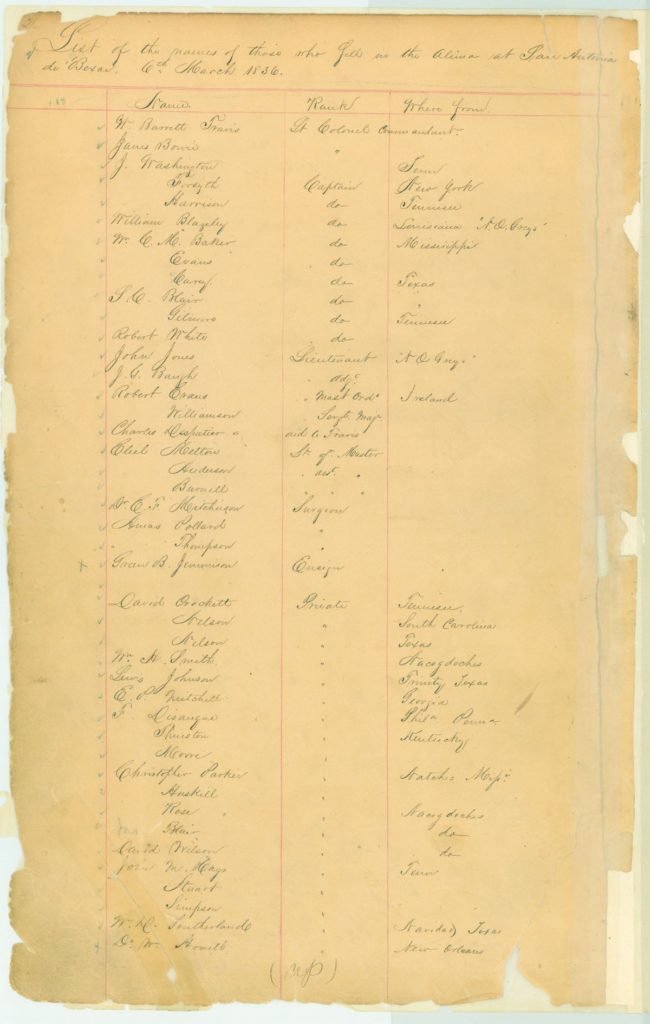

The McArdle Notebooks, Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Just before dawn on March 6, 1836, Santa Anna ordered an assault on the Alamo, and the defenders were overpowered within a few hours. Travis died early in the battle on the north wall from a single bullet in the head, one of the first to die. His death was witnessed by his slave Joe, who escaped from San Antonio. Travis’s body, along with those of the other defenders, was burned at the Alamo. The nature of Travis’s death elevated him from mere soldier status to that of a hero of Texas history.